Best Practices for Engineering ML Pipelines - Part 1

Posted on Wed 03 March 2021 in machine-learning-engineering

The is the first in a series of articles demonstrating how to engineer a machine learning pipeline and deploy it to a production environment. We’re going to assume that a solution to a ML problem already exists within a Jupyter notebook, and that our task is to engineer this solution into an operational ML system, that can train a model, serve it via a web API and automatically repeat this process on a schedule when new data is made available.

The focus will be on software engineering and DevOps, as applied to ML, with an emphasis on ‘best practices’. All of the code developed in each part of this project, is available on GitHub, with a dedicated branch for each part, so you can explore the code in its various stages of development.

This first part is focused on how to setup a ML pipeline engineering project and covers:

- Basic solution architecture.

- How to structure the codebase (and repo).

- Setting-up automated testing and static code analysis tools.

- Making an initial “”Hello, Production” deployment.

- Configuring a CI/CD pipeline.

Table of Contents

Reviewing the Business Problem

A manufacturer of industrial spare-parts wants the ability to give its customers an estimate for the time it could take to dispatch an order. This depends on how many existing orders have yet to be processed, such that customers ordering late on a busy day can encounter unexpected delays, which sometimes leads to complaints; this is an exercise in keeping customers happy by managing their expectations.

Orders are placed on a B2B eCommerce platform, that is developed and maintained by the manufacturer’s in-house software engineering team. The product manager for the platform wants the estimated dispatch time to be presented to the customer (through the UI), before they place an order.

Reviewing the Technical Problem

A data scientist has worked on this (regression) task and has handed us the Jupyter notebook containing their solution. They have concluded that optimal performance can be achieved by training on the preceding week’s orders data, so the model will have to be re-trained and redeployed on a weekly basis.

At the end of each week, the data engineering team deliver a new tranche of training data, as a CSV file on cloud object storage (AWS S3). The platform engineering team want access to order-dispatch estimates via a web service with a simple REST API, and have supplied us with an example request and response (reproduced below). The platform and data engineering teams both deploy their systems and services to AWS, and we too are required to deploy our solution (the pipeline) to AWS.

Example Prediction Request JSON

{

"product_code": "SKU001",

"orders_placed": 112

}

Example Prediction Response JSON

{

"est_hours_to_dispatch": 5.321,

"model_version": "0.1"

}

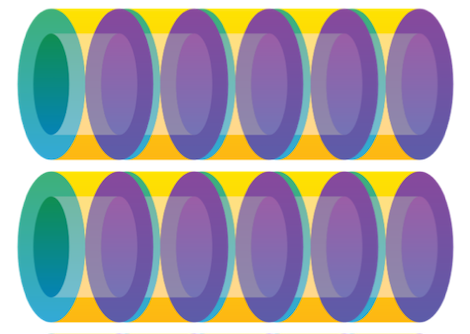

Solution Architecture

The architecture for the target solution is outlined above - the workflow is as follows:

- Every Friday night at 2300 a new batch of training data is added to an S3 bucket in CSV format.

- After the new data arrives, a pipeline needs to be triggered that will train a new model and then deploy it, tearing-down the previous prediction service in the process (with zero downtime in-between).

The pipeline will be split into two stages, each of which will be implemented as an executable Python module:

- train model - downloads the latest tranche of data from object storage, trains a model and then persists the model to object storage.

- serve model - downloads the latest trained model and then starts a web server that exposes a REST API endpoint that serves requests for dispatch duration predictions.

The pipeline will be deployed in containers to AWS EKS (managed Kubernetes cluster), using Bodywork.

Structuring the Pipeline Project

The files in the project’s git repository are organised as follows:

root/

|-- .circleci/

|-- config.yml

|-- notebooks/

|-- time_to_dispatch_model.ipynb

|-- requirements_nb.txt

|-- pipeline/

|-- __init__.py

|-- serve_model.py

|-- train_model.py

|-- utils.py

|-- tests/

|-- __init__.py

|-- test_train_model.py

|-- test_serve_model.py

|-- requirements_cicd.txt

|-- requirements_pipe.txt

|-- flake8.ini

|-- mypy.ini

|-- tox.ini

|-- bodywork.yaml

.circleci/config.ymlcontains the configuration for the project’s CI/CD pipeline (using CircleCI). We’ll discuss in more depth later on.notebooks/*- has all of the Jupyter notebooks detailing the ML solution to the business problem.pipeline/*has all Python modules that define the pipeline.tests/*contains Python modules defining automated tests for the pipeline.requirements_cicd.txtlists the Python packages required by the CI/CD pipeline - e.g. for running tests and deploying the pipeline.requirements_pipe.txtlists the Python packages required by the pipeline - e.g. Scikit-Learn, FastAPI, etc.flake8.ini&mypy.iniare configuration files for Flake8 code style enforcement and MyPy static type checking.tox.iniprovides configuration for the Tox test automation framework.bodywork.yamlis the Bodywork deployment configuration file.

Setting-Up the Local Dev Environment

We’ve split the various Python package requirements into separate files:

requirements_pipe.txtcontains the packages required by the pipeline.requirements_cicd.txtcontains the packages required by the CICD pipeline.notebooks/requirements_nb.txtcontains the package required to run the notebook.

We’re planning to deploy the pipeline using Bodywork, which currently targets the Python 3.9 runtime, so we create a Python 3.9 virtual environment in which to install all requirements.

$ python3.9 -m venv .venv

$ source .venv/bin/activate

$ pip install -r requirements_pipe.txt

$ pip install -r requirements_cicd.txt

$ pip install -r requirements_nb.txt

Setting-Up the Testing Framework

We’re going to use pytest to support test development and we’re going to run them via the Tox test automation framework. The best way to get this operational, is to write some skeleton code for the pipeline that can be covered by a couple of basic tests. For example, at a trivial level the train_model.py batch job should provide us with some basic logs, whose existence we can test for in test_train_model.py. Taking a Test-Driven Development (TDD) approach, we start with the test in test_train_model.py,

from _pytest.logging import LogCaptureFixture

from pipeline.train_model import main

def test_main_execution(caplog: LogCaptureFixture):

main()

logs = caplog.text

assert "Starting train-model stage." in logs

Where we use pytest’s caplog fixture to capture logs messages. We now provide the implementation in train_model.py,

from pipeline.utils import configure_logger

log = configure_logger()

def main() -> None:

log.info("Starting train-model stage.")

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()

Where configure_logger configures a Python logger that will be common to both train_model.py and serve_model.py.

Similarly for the serve_model.py module, we can write a trivial test for the REST API endpoint in test_serve_model.py,

from fastapi.testclient import TestClient

from pipeline.serve_model import app

test_client = TestClient(app)

def test_web_api_returns_valid_response_given_valid_data():

prediction_request = {"product_code": "SKU001", "orders_placed": 100}

prediction_response = test_client.post(

"/api/v0.1/time_to_dispatch", json=prediction_request

)

assert prediction_response.status_code == 200

assert "est_hours_to_dispatch" in prediction_response.json().keys()

assert "model_version" in prediction_response.json().keys()

def test_web_api_returns_error_code_given_invalid_data():

prediction_request = {"product_code": "SKU001", "foo": 100}

prediction_response = test_client.post(

"/api/v0.1/time_to_dispatch", json=prediction_request

)

assert prediction_response.status_code == 422

assert "value_error.missing" in prediction_response.text

This loads the FastAPI test client and uses it to verify that sending a request with valid data results in a response with a HTTP status code of 200, but sending invalid data results in a HTTP 422 error (see this for more information on HTTP status codes). In serve_model.py we implement the code to satisfy these tests,

from typing import Dict, Union

import uvicorn

from fastapi import FastAPI, status

from pydantic import BaseModel

app = FastAPI(debug=False)

class Data(BaseModel):

product_code: str

orders_placed: float

class Prediction(BaseModel):

est_hours_to_dispatch: float

model_version: str

@app.post(

"/api/v0.1/time_to_dispatch",

status_code=status.HTTP_200_OK,

response_model=Prediction,

)

def time_to_dispatch(data: Data) -> Dict[str, Union[str, float]]:

return {"est_hours_to_dispatch": 1.0, "model_version": "0.1"}

if __name__ == "__main__":

uvicorn.run(app, host="0.0.0.0", workers=1)

If you’re unfamiliar with how FastAPI uses Python type hints and Pydantic to define JSON schema, then take a look at the FastAPI docs.

You can run all tests in the tests folder using,

$ pytest

Or isolate a specific test using the -k flag, for example,

$ pytest -k test_web_api_returns_valid_response_given_valid_data

Using Tox for Test Automation

Tox is a test automation framework that helps to manage groups of tests, together with isolated environments in which to run them. Configuration for Tox is defined in tox.ini , which is reproduced below.

[tox]

envlist = {py39}_{unit_and_functional_tests,static_code_analysis}

[testenv]

skip_install = true

deps =

-rrequirements_cicd.txt

-rrequirements_pipe.txt

commands =

unit_and_functional_tests: pytest tests/ --disable-warnings {posargs}

static_code_analysis: mypy --config-file mypy.ini

static_code_analysis: flake8 --config flake8.ini pipeline

Calling Tox from command line,

$ tox

Will run every set of tests - those defined in the commands tagged with unit_and_functional and static_code_analysis - for every chosen environment, which in this case is just Python 3.9 (py39). This environment will have none of the environment variables or commands that are present in the local shell, unless they’ve been specified (we haven’t), and can only use the packages specified in requirements_cicd.txt and requirements_pipe.txt. Individual test-environment pairs can be executed using the -e flag - for example,

$ tox -e py39_static_code_analysis

Will only run Flake8 and MyPy (static code analysis tools) and leave out the unit and functional tests. For more information on working with Tox, see the documentation.

Testing Manually

Sometimes you just need to test on a ad hoc basis, by running the modules, setting breakpoints, etc. You can run the batch job in train_model.py using,

$ python -m pipeline.train_model

Which should print the following to stdout,

2021-07-05 18:52:24,264 - INFO - train_model.main - Starting train-model stage.

Similarly, the web API defined in serve_model can be started with,

$ python -m pipeline.serve_model

Which should print the following to stdout,

INFO: Started server process [21974]

INFO: Waiting for application startup.

INFO: Application startup complete.

INFO: Uvicorn running on http://0.0.0.0:8000 (Press CTRL+C to quit)

And make the API available for testing locally - e.g., issuing the following request from the command line,

$ curl http://localhost:8000/api/v0.1/time_to_dispatch \

--request POST \

--header "Content-Type: application/json" \

--data '{"product_code": "001", "orders_placed": 10}'

Should return,

{

"est_hours_to_dispatch": 1.0,

"model_version": "0.1"

}

As defined in the tests. FastAPI will also automatically expose the following endpoints on your service:

- http://localhost:8000/docs - OpenAPI documentation for the API, with a UI for testing.

- http://localhost:8000/openapi.json - the JSON schema for the API.

Creating a Deployment Environment

Here at Bodywork HQ, we’re advocates for the “Hello, Production” school-of-thought, that encourages teams to make the deployment of a skeleton application (such as the trivial pipeline sketched-out in this article), one of the first tasks for any new project. As we have written about before, there are many benefits to taking deployment pains early on in a software development project, and then using the initial deployment skeleton as the basis for rapidly delivering useful functionality into production.

We’re planning to deploy to Kubernetes using Bodywork, but we appreciate that not everyone has easy access to a Kubernetes cluster for development. If this is your reality, then the next best thing your team could do, is to start by deploying to a local test cluster, to make sure that the pipeline is at least deploy-able. You can get started with a single node cluster on your laptop, using Minikube - see our guide to get this up-and-running in under 10 minutes.

The full description of the deployment is contained in bodywork.yaml, which we’ve reproduced below.

version: "1.1"

pipeline:

name: time-to-dispatch

docker_image: bodyworkml/bodywork-core:3.1

DAG: train_model >> serve_model

stages:

train_model:

executable_module_path: pipeline/train_model.py

cpu_request: 0.25

memory_request_mb: 100

batch:

max_completion_time_seconds: 60

retries: 2

serve_model:

executable_module_path: pipeline/serve_model.py

requirements:

- fastapi==0.65.2

- uvicorn==0.14.0

cpu_request: 0.25

memory_request_mb: 100

service:

max_startup_time_seconds: 90

replicas: 2

port: 8000

ingress: true

logging:

log_level: INFO

This describes a deployment with two stages - train-model and serve-model - that are executed one after the other, as described in pipeline.DAG. For more information on how to configure a Bodywork deployment, checkout the User Guide.

Once you have access to a test cluster, configure it for Bodywork deployments,

$ bw configure-cluster

And then deploy the workflow directly from the GitHub repository (so make sure all commits have been pushed to your remote branch),

$ bw create deployment https://github.com/bodywork-ml/ml-pipeline-engineering --branch part-one

We like to watch our deployments rolling-out using the Kubernetes dashboard, as you can see in the video clip below.

Once the deployment has completed successfully, retrieve the details of the prediction service,

$ bw get deployment time-to-dispatch serve-model

You can manually test the deployed prediction endpoint using,

$ curl http://CLUSTER_IP/time-to-dispatch/serve-model/api/v0.1/time_to_dispatch \

--request POST \

--header "Content-Type: application/json" \

--data '{"product_code": "001", "orders_placed": 10}'

Which should return the same response as before,

{

"est_hours_to_dispatch": 1.0,

"model_version": "0.1"

}

See our guide to accessing services for information on how to determine CLUSTER_IP.

Configuring CI/CD

Now that the overall structure of the project has been created, all that remains is to put in-place the processes required to get new code merged and deployed as quickly and efficiently as possible. The process of getting new code merged on an ad hoc basis, is referred to as Continuous Integration (CI), while getting new code deployed as soon as it is merged, is known as Continuous Deployment (CD). The workflow we intend to impose is outlined in the diagram above. Briefly:

- Pushing changes (commits) to the

masterbranch of the repository is forbidden. All changes should first be raised as merge (or pull) requests, that have to pass all automated testing and some kind of peer review process (e.g. a code review), before they can be merged to themasterbranch. - Once changes are merged to the master branch, they can be deployed.

Here at Bodywork HQ we use GitHub and CircleCI to run this workflow. Branch protection rules on GitHub are used to prevent changes being pushed to master, unless automated tests and peer review have been passed. CircleCI is a paid-for CI/CD service (with an outrageously generous free-tier) that automatically integrates with GitHub to enable jobs (such as automated tests) to be triggered automatically following merge requests, or changes to the masterbranch, etc. Our CircleCI pipeline is defined in .circleci/config.yml and reproduced below.

version: 2.1

orbs:

aws-eks: circleci/aws-eks@1.0.3

jobs:

run-static-code-analysis:

docker:

- image: circleci/python:3.9

steps:

- checkout

- run:

name: Installing Python dependencies

command: pip install -r requirements_cicd.txt

- run:

name: Running tests

command: tox -e py39_static_code_analysis

run-tests:

docker:

- image: circleci/python:3.9

steps:

- checkout

- run:

name: Installing Python dependencies

command: pip install -r requirements_cicd.txt

- run:

name: Running tests

command: tox -e py39_unit_and_functional_tests

trigger-bodywork-deployment:

executor:

name: aws-eks/python

tag: "3.9"

steps:

- aws-eks/update-kubeconfig-with-authenticator:

cluster-name: bodywork-dev

- checkout

- run:

name: Installing Python dependencies

command: pip install -r requirements_cicd.txt

- run:

name: Trigger Deployment

command: bodywork create deployment https://github.com/bodywork-ml/ml-pipeline-engineering --branch master

workflows:

version: 2

test-build-deploy:

jobs:

- run-static-code-analysis:

filters:

branches:

ignore: master

- run-tests:

requires:

- run-static-code-analysis

filters:

branches:

ignore: master

- trigger-bodywork-deployment:

filters:

branches:

only: master

Although this configuration file is specific to CircleCI, it will be easily recognisable to anyone who’s ever worked with similar services such as GitHub Actions, GitLab CI/CD, Travis CI, etc. In essence, it defines the following:

- Three separate jobs:

run-static-code-analysis,run-testsandtrigger-bodywork-deployment. Each of these run in their own Docker container, with the project’s GitHub repo checked-out and any Python dependencies installed. Thetrigger-bodywork-deploymentjob is set to run on a custom AWS-managed image (or ‘Orb’), that comes with additional tools for working with AWS’s EKS (managed Kubernetes) service, which is our ultimate deployment target. - A workflow that is triggered upon every merge request:

run-static-code-analysisis first executed, which runstox -e py39_static_code_analysis. If this passes, then therun-testsjob is executed, which runstox -e py39_unit_and_functional_tests. If this also passes, then CircleCI will mark this workflow as ‘passed’ and report this back to GitHub (see below). - A workflow that is triggered upon every merge to

master:trigger-bodywork-deploymentis the only job in this pipeline, which uses Bodywork to deploy the latest pipeline (using rolling updates to maintain service availability).

Wrapping-Up

In the first part of this project we have expended a lot of effort to lay the foundations for the work that is to come - developing the model training job, the prediction service and deploying these to a production environment where they will need to be monitored. Thanks to automated tests and CI/CD, our team will be able to quickly iterate towards a well-engineered solution, with results that can be demonstrated to stakeholders early on.